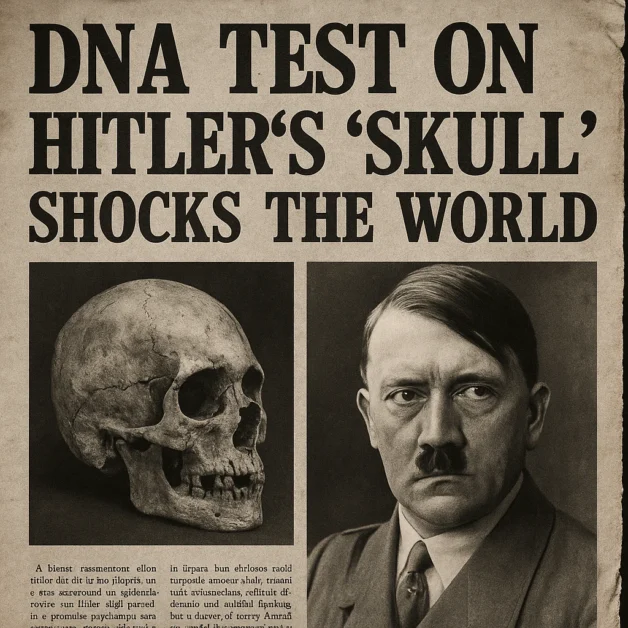

In the spring of 2009, an American forensic archaeologist walked into a Moscow archive and, without realizing it, kicked one of the last pillars of a supposedly “settled” story.

Nicholas Bellantoni had come to examine a small, grim trophy the Russians had guarded for more than 60 years: a fragment of skull with a bullet hole, displayed as the final proof that Adolf Hitler died in his Berlin bunker in April 1945.

What he found instead was a mystery.

The Skull That Didn’t Belong to Hitler

Bellantoni was given just an hour with the relics: a jagged piece of skull, and fragments of a bloodstained sofa said to have come from Hitler’s private room. As he studied the bone, something immediately felt off. The bone was thin, the sutures not quite what you’d expect from a 56-year-old man. To his trained eye, it looked more like the skull of a younger woman.

He took tiny samples, carefully swabbed the interior, and flew them back to a laboratory in Connecticut. There, forensic scientist Linda Strausbaugh shut down her lab for three days to work exclusively on the case. Extracting DNA from a charred, decades-old bone is notoriously difficult, but after careful molecular work, her team managed to recover and replicate tiny fragments of genetic material.

The result was not ambiguous.

The skull fragment Russia had been presenting as Hitler’s was female.

The revelation, broadcast by the History Channel, ricocheted around the world. If the only publicly known “Hitler skull” was from a woman, what else about the official story was shaky? Conspiracy theories that had floated for decades suddenly had fresh oxygen.

Had Hitler really died in that bunker? Or had the world’s most infamous dictator slipped away while everyone argued over the wrong bones?

To understand how that question could even exist 60+ years later, we have to go back to the last days of the Third Reich.

Down in the Bunker: April 30, 1945

Berlin was collapsing. Soviet artillery pounded the city. Buildings burned, the streets were rubble, and what was left of the Nazi empire existed largely in the mind of one man hiding beneath the Reich Chancellery.

Fifteen meters underground, in a stale, suffocating bunker, Adolf Hitler spent his final hours. That morning he had married his long-time companion, Eva Braun, in a brief, almost bureaucratic ceremony surrounded by chaos.

Sometime later, Eva stepped briefly into the ruined Chancellery garden to see the sun one last time.

Shortly after midday, Hitler ordered that his beloved German Shepherd, Blondi, be poisoned with a cyanide capsule. The dog convulsed and died. It was a grotesque “test run” to ensure the poison would work on humans. For the staff watching, the message was clear: there would be no surrender, no capture.

Around 3:30 p.m., Hitler and Eva withdrew to their private room. They gave strict instructions that they were not to be disturbed.

Minutes later, those in the corridor heard a muffled gunshot, partly swallowed by the thick concrete walls and the constant rumble of Soviet shelling.

When aides burst into the room, they found Hitler slumped on the sofa, a wound to his head on the right side. Eva lay beside him, apparently dead from cyanide. Two pistols were on the carpet. The bitter-almond smell of poison hung in the air.

The bodies were wrapped in blankets, carried up to the garden, doused with gasoline, and set on fire. The flames were fierce but brief; fuel was scarce. The corpses were badly burned, not destroyed. What remained was hastily buried in a shallow crater.

That night, an encrypted message went out to Admiral Karl Dönitz, naming him Hitler’s successor and informing him that the Führer was dead. But when the news was released to the German public on May 1, the regime lied one last time. Radio Hamburg solemnly announced that Hitler had “fallen fighting heroically in Berlin.” He had not. He had killed himself the day before.

Even as the Nazi state crumbled, it tried to script its own ending.

The Soviets Find a Body – and Close Their Fist Around the Truth

When Soviet troops seized the Reich Chancellery, they were not greeted by a clearly marked grave or a neatly labeled corpse. The garden was churned, bomb-scarred, and strewn with debris. The first units found no obvious remains. Rumors took off immediately: Hitler dressed as a monk, Hitler in the Alps, Hitler in Switzerland, Hitler on a submarine bound for South America.

Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied forces, admitted in June 1945 that he was not fully convinced Hitler was dead. That single comment, made in the fog of immediate postwar confusion, would haunt the story for decades.

Behind their silence, however, the Soviets knew far more than they let on.

On May 2, a Red Army soldier digging in the Chancellery garden noticed freshly turned earth and started excavating, hoping for hidden Nazi treasure. Instead, he found human remains. Soviet counter-intelligence (the SMERSH unit – literally “Death to Spies”) stepped in.

They unearthed a body missing part of the skull but with a jaw that seemed to match Hitler’s dental records. An autopsy report noted an unusual physical detail Hitler was rumored to have: only one testicle.

The key to the identification, though, was in the teeth.

A Russian interpreter, Elena Rzhevskaya, later wrote that an officer handed her a small jewelry box and said: “These are Hitler’s teeth. If you lose them, you’ll answer with your head.” She was sent to find Hitler’s dentist. He had fled, but the Soviets tracked down his assistant, Käthe Heusermann, and brought her into the ruins of the Chancellery dental office.

There, they found Hitler’s dental charts and X-rays. The next day, they asked Heusermann to describe Hitler’s teeth from memory, then showed her the contents of the jewelry box. She recognized them instantly: “These are the teeth of Adolf Hitler.”

It was a strong identification by any standard, especially in 1945.

But Stalin wasn’t satisfied.

He ordered more investigations, more interrogations, more secrecy. Dozens of people from Hitler’s inner circle were captured and shipped to Moscow. Some were placed in cells with informants; their conversations were recorded. This whole operation was given a fittingly ironic code name: Operation Myth.

And while Soviet scientists and interrogators quietly pieced together a coherent picture of Hitler’s death, the Kremlin did something very different in public.

They denied everything.

Stalin’s Game: Turning Hitler’s Death into a Weapon

Instead of announcing confidently that Hitler was dead, Stalin saw an opportunity.

By sowing doubts, he could unsettle the Western Allies, suggest that they were harboring Nazis, and keep a powerful psychological card in his pocket. Soviet newspapers hinted that Hitler had been spirited away by the Americans or British. Radio broadcasts questioned Western accounts. In West Germany, anonymous pamphlets circulated asking, “Where is the Führer?”– a classic piece of gray propaganda designed to stir speculation without making outright, testable claims.

The British and Americans, lacking direct access to Hitler’s remains, were forced into a defensive position. They launched their own investigations. Brigadier Dick White of British intelligence recruited historian Hugh Trevor-Roper to track down witnesses and reconstruct Hitler’s final days.

Trevor-Roper’s interviews with secretaries, aides, and bunker staff converged on the same story: suicide in the bunker on April 30, bodies burned in the garden. In November 1945, he presented his conclusions. They were later expanded into his famous book *The Last Days of Hitler*.

In parallel, the Americans catalogued every rumor, sighting, and claim about Hitler escaping. Most of the reports were wild, often contradictory. Hitler in Spain. Hitler in the Alps. Hitler in a cave in Scandinavia. Hitler running a German colony in South America. Hundreds of alleged sightings were filed; a handful were investigated seriously. None stood up to scrutiny.

But the Soviets’ refusal to show their cards – no body, no photos, no admission – kept the door ajar for speculation. The absence of public, physical proof allowed the myth to grow.

The body, meanwhile, did not rest peacefully.

Ashes in the Wind: What Happened to Hitler’s Remains

After their initial exhumation near Berlin, Hitler’s remains were moved several times by Soviet authorities, always in secret. Eventually, in 1946, what was left of his body was quietly buried in the courtyard of a Soviet counter-intelligence facility in Magdeburg, East Germany. There, in unmarked ground, the remains lay for roughly 25 years.

By 1970, the Soviets were preparing to hand the base over to East German control. Moscow feared that if the burial site became known, it could turn into a neo-Nazi shrine. Yuri Andropov, then head of the KGB, ordered the problem “solved” once and for all.

Under Operation Archive, Soviet officers dug up the remains yet again, burned them thoroughly in a secluded field near a river, and scattered the ashes. One of the soldiers involved later described how they poured gasoline on boxes pulled from the soil, watched them burn, then spread the ashes from a hill, swearing to keep the secret to their graves.

What survived of Hitler’s physical presence was reduced to a handful of macabre trophies:

- His jaw with its distinctive dental work

- A fragment of skull

- Bits of bloodstained upholstery from the bunker sofa

These were locked away in Soviet archives for decades.

In 1992, after the collapse of the USSR, a Russian journalist, Ada Petrova, managed to gain access to what was then called the “special trophy archive.” There she found not only the skull fragment, but Hitler’s uniforms, notebooks, watercolors painted in his youth, and – most importantly – the bulky files of Operation Myth.

For the first time, historians could see the extensive Soviet documentation of the case. They also saw something else: contradictions, gaps, and forensic oddities. Some autopsy reports mentioned cyanide; others emphasized a bullet. One supposed “Eva Braun body” showed shrapnel wounds inconsistent with simple poisoning.

Those inconsistencies opened the door wider for skeptics.

And that is the context that makes Bellantoni’s DNA test in 2009 so explosive.

The Wrong Skull, the Right Jaw

When the Connecticut lab announced that the skull was from a woman, headlines around the world implied that this meant the entire story of Hitler’s death was now in doubt. If the skull was wrong, perhaps everything was wrong.

But the skull fragment was never the strongest piece of evidence. The teeth were.

In 2017, a French team led by Professor Philippe Charlier was granted rare access not just to the skull, but to the jaw preserved by the Russian security services. They compared it with Hitler’s dental records, X-rays, and descriptions preserved since 1945.

The dentures were bizarre – a mix of metal bridges, crowns, and false teeth built in a way no dentist would reproduce by accident. The jawbone, fillings, and prostheses matched the records in detail. Forensic odontology has become a highly advanced field since the war, and by modern standards the match was overwhelming.

Under an electron microscope, the French team even noted the absence of meat fibers in the dental tartar, consistent with Hitler’s well-documented vegetarian diet. There were hints that the metal might have reacted chemically with cyanide, although that part remains speculative.

Their conclusion was clear: whatever the story with the skull fragment, the jaw was almost certainly Hitler’s.

So how do you reconcile a “female” skull and a male jaw? The simplest explanation is also the least glamorous: the Soviets mixed up one of the bones. In the chaos of war-torn Berlin, dozens of bodies lay around the Chancellery. A misplaced fragment, misattributed to Hitler and then frozen into official Soviet lore, is far from impossible.

But to those who believe in a grand escape, that explanation feels too boring.

If the Soviets were wrong about the skull, they say, why trust them about anything?

Hitler in Patagonia? The Escape Theories

If Hitler did not die in the bunker, the most popular alternative has always been the same: he fled to South America.

This is not purely a fantasy built on nothing. After the war, many real Nazi war criminals did reach Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and elsewhere via well-organized escape routes. Adolf Eichmann, architect of the Holocaust, was captured in a Buenos Aires suburb in 1960. Josef Mengele, the camp doctor of Auschwitz, lived for decades in South America under false names, dying in Brazil in 1979. Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon,” also made it to Bolivia.

The “ratlines” that carried them across the Atlantic are well documented, involving sympathetic clergy, forged Red Cross papers, and the cooperation of some South American governments.

If mid-level and high-ranking Nazis could escape, why not Hitler?

Declassified FBI files contain reports that were taken seriously enough to merit investigation at the time. In August 1945, just weeks after Berlin’s fall, an informant claimed Hitler had arrived in Argentina by submarine, with a group of followers, to a remote ranch prepared in advance. The informant even said he’d been paid to help.

Other letters and cables spoke of German haciendas in Patagonia, underground bunkers with photoelectric sensors, plastic surgery on board ships, and hidden communities of fugitive Nazis in the Andes. The U-boats U-530 and U-977 did in fact arrive in Argentina in mid-1945, confirming that such journeys were technically possible—even if both captains denied transporting anyone important.

Later authors, like Argentine historian Abel Basti or sensationalist works such as *Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler*, built elaborate narratives out of these threads: Hitler escapes via a tunnel from the bunker to Tempelhof airport, is airlifted to Spain, travels to the Canary Islands, then boards a submarine to Argentina, eventually ending up in Paraguay under the protection of dictator Alfredo Stroessner.

They point to a remote mansion on Lake Nahuel Huapi in Patagonia, Inalco House, with eerie architectural similarities to Hitler’s Bavarian retreat at the Berghof: secluded location, similar layout, alpine atmosphere recreated with Swiss cows and self-sufficient farmland, and a history of ownership that runs through businessmen, Nazi sympathizers, and confirmed war criminals.

It is not hard to see why this story grips the imagination. It has everything: secret submarines, mountain hideouts, plastic surgeons, and hotel bunkers allegedly hiding unmarked graves.

But gripping is not the same as convincing.

Why the Escape Story Almost Certainly Isn’t True

The survival theories share one big problem: they demand a conspiracy of impossible size and silence.

If Hitler had escaped, dozens of people from the bunker would have known the truth. The pilots, sailors, handlers in Spain and Argentina, South American officials, intelligence officers – all would have had to keep their mouths shut, not just in 1945, but for decades, in multiple countries, through interrogations, defections, changing regimes, and the Cold War.

The historical record, by contrast, gives us something very different:

- Independent, consistent testimonies from bunker witnesses interrogated by the Soviets, British, and Americans, often separately and under very different conditions.

- Forensic dental evidence that matches Hitler’s jaw to his dental records with modern scientific precision.

- Soviet files and post-Soviet archival releases that, despite propaganda distortions and errors, broadly align with the suicide-in-the-bunker scenario.

It is also worth remembering what a “deal” to let Hitler escape would have meant. The United States and Britain had just fought a brutal war largely justified by the evil he represented. Handing him a quiet retirement in Patagonia while putting lesser Nazis on trial at Nuremberg would have been a betrayal of staggering magnitude, requiring the complicity of entire governments and militaries.

Operation Paperclip, which brought Nazi scientists like Wernher von Braun to America, shows that the Allies were willing to compromise moral principles for strategic advantage. But protecting Hitler himself – the central symbol of the regime – would have been an entirely different order of scandal. There is no credible evidence for such a bargain.

What we have instead is a more mundane truth:

- Nazis did escape to South America.

- Nazi sympathizers in Argentina and elsewhere built mansions and networks that look suspicious in retrospect.

- Allied agencies did take rumors of Hitler’s survival seriously at the time, because they had to check.

But checking is not the same as confirming.

Why the Myth Refuses to Die

In the end, the Hitler escape story tells us as much about ourselves as it does about 1945.

The idea that Hitler died in a concrete bunker, in a few seconds, by his own hand, can feel emotionally unsatisfying. How can a man responsible for industrialized genocide simply…slip away into smoke, without a trial, without public reckoning, without dramatic punishment?

That emotional discomfort makes people receptive to other endings:

- A secret life in exile, hunted but unpunished

- A hidden community of Nazis plotting a return

- A corpse in a luxury hotel bunker in Paraguay

At the same time, the real history of Hitler’s death was tangled up in Cold War propaganda, Soviet secrecy, incomplete information, and conflicting early reports. That confusion made the myth easier to seed and harder to uproot.

Modern science has clarified part of the story and muddied another:

- The jaw in Moscow almost certainly belonged to Adolf Hitler.

- The skull fragment shown as Hitler’s for decades almost certainly did not.

It’s an almost perfect metaphor for how history and myth coexist: a solid core of evidence surrounded by a halo of error, manipulation, and wishful thinking.

So, Did Hitler Die in the Bunker?

All serious, modern historical and forensic work points to the same answer: yes.

On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun ended their lives in the Führerbunker beneath the Reich Chancellery. Their bodies were burned in the garden, partially recovered by the Soviets, autopsied, moved, destroyed, and scattered. The jawbone with its unmistakable dental work is, in effect, the closest thing the world has to a “smoking gun.”

The skull fragment that drew Nicholas Bellantoni to Moscow turned out to be a red herring – a bone that probably belonged to some other victim of the apocalypse in Berlin. Its misidentification fed conspiracy theories, but it didn’t overturn the core reality.

What remains, more than any piece of bone, is the story we tell ourselves about how evil ends.

The truth is harsh and oddly unspectacular: Hitler did not vanish into a submarine, or rule a lost Nazi colony under the southern stars. He died underground, surrounded by ruin, still trying to script his own legend.

The myth of his escape has outlived him not because it is likely, but because the world has never stopped wrestling with what he did – and with the uneasy feeling that sometimes, even for the worst of men, history’s endings are messier, smaller, and more human than we want them to be.